Fortunately, today the wow effect that words such as “neuromarketing” and “neuroscience” have aroused so far is fading and only what is solid and applicable in this discipline remains. If in this context many will be sorry that they will no longer be able to apply their manipulation logics, we are convinced that we will benefit from it because finally it will be possible to do applied science without having to explain that the “buy button” is a deplorable illusion.

What neuromarketing is (not) for

We are convinced that today there are two main elements that contribute to the interest in neuromarketing and neuroscience more generally. One element is decidedly negative, while the other potentially positive.

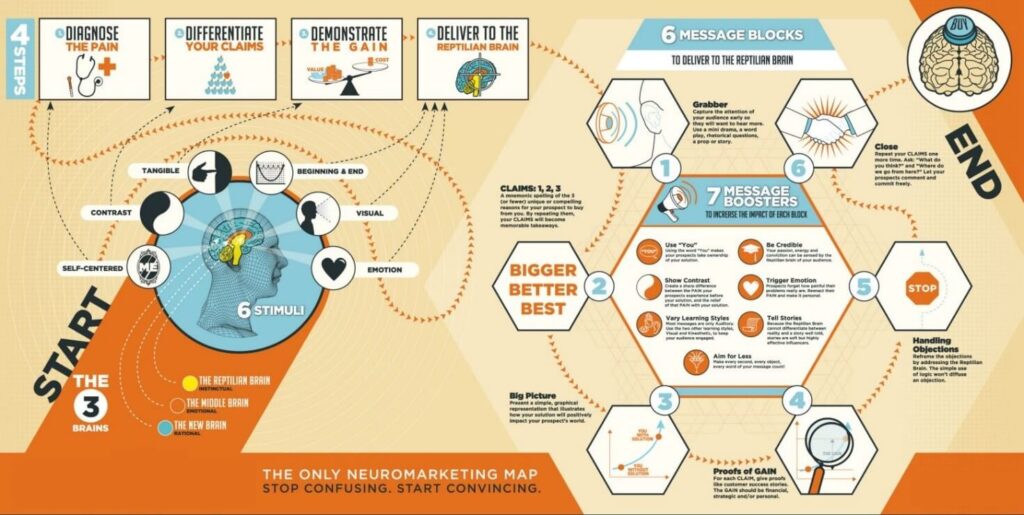

Newcomers to neuromarketing are inundated with articles promising extraordinary results. Incredible worlds lie ahead which, with a simple recipe based on electroencephalograms and emotions, can allow you to earn all that you have not been able to with years of hard work. You can squeeze your buyers, you can manipulate them and, once finished, you can push yourself in search of new customers. How? Apparently it is as easy as pressing people’s “Buy Button”. The journey is so simple that there is even a map with rules similar to those of the Goose Game, with messages to be sent to the “Reptilian Brain”.

Needless to say that those who make themselves prophets of this creed have, from our point of view, the same reliability and guarantees typical of other sectors such as horoscopes or fortune tellers who know the winning lottery numbers and are willing to share them with you, and only you, for a reasonable price.

Obviously, what we have told you is the negative aspect in our eyes. We find ourselves in a situation where the ending “neuro” is exasperated and used to the extreme as a marketing element, enormously impacting people’s perceptions. This happens because of what, in the world of psychology, is called “framing“. Thus, words with a highly attractive effect (but often without substance) came about such as neurobranding, neuropackaging, neurocopywriting, neuroweb, neuroselling, neurogastronomy.

Now, let’s do a simple exercise to understand if this logic can make an impact from a marketing point of view. Try to imagine the price list for a copywriting activity, compared to one for neurocopywriting. Which one do you expect costs more?

The curious thing is that the activity that is presumably carried out in these sectors is always the same. It is only the context of use that changes. It is as if we had an instrument at our disposal (the meter for example) and we changed its name according to its use (distance-meter, height-meter, sport-meter, etc.). The birth of these hypothetical micro-sectors is proof that we are trying to bring an increase in the perception of value without truly bringing any additional value.

All this inevitably ends up imploding. It’s like a kind of Ponzi scheme, without the guarantee of being able to give big gains to the first investors. At some point, if we limit ourselves to working on the mere perception of value, but said value is left unchanged, companies will begin to wonder if their investment makes sense, inevitably diverting their capital to new fronts.

Neuromarketing today

Today, according to our research, we are at the point where players who exploit the marketing part linked to the world of neuroscience are decreasing in the market (although, alas, some remain), and a sector is emerging that instead pursues the other element that generates interest in this sector: objective and predictive models.

These characteristics are not exclusive to neuromarketing. Rather, they are contexts from the world of psychophysiology and neuroscience in general (and beyond). These disciplines, in fact, allow for reasoning that is not available within the classic survey models (questionnaires, interviews, etc.). It doesn’t mean they’re better or worse. It simply means they’re different.

And this is not about machine learning or artificial intelligence either (other linguistic cases robbed of their true, undeniable value by the vulgar marketing). They are simply statistical applications that are based on models we already know. Let’s try an example.

By knowing some characteristics about an adult (in particular, age, state of health, etc.), one could bet that their resting heart rate is between 60 and 90 (Daniel et al, 2005). While if we estimate that of a child I would suggest betting between 80 and 100 beats per minute. It is not a very risky bet as there is a predictive model that tells us that this is normally the case.

Similarly, if I measured my own heart rate every day at 10:00AM I would get my average result. I could therefore predict with statistical certainty that the next day, if I do not significantly change behaviour, I will have approximately the same heart rate. So far everything should be clear.

Now comes the interesting part. What does “significantly change behaviour” mean? For example, in the case of heart rate, consistent coffee consumption could occur (I drank 4 cups in the previous 2 hours). This will inevitably lead to a greater cardiac response. Let’s assume an increase of 20 beats. The question I now ask myself is: “would this happen to anyone who drinks 4 cups of coffee or does it only happen to myself?”

There are variables that modify the response (such as age, body weight, pregnancy, drug intake, and liver health), but we all respond to this stimulus (although not everyone is aware of it).

Now try to imagine this dynamic, moving it into a context in which brain processes related to emotions are evaluated (for example, frontal asymmetry), which literature has shown to be involved in the processes of choice.

Research and neuroscience to design better experiences: the TSW approach

In fact, what we do in our research is to metaphorically administer coffee (for example, TV commercials) and assess whether it has a systematic impact (modification of brain activity), consequently quantifying this impact (increase in FAA). Because we know that if our ‘coffee’ has managed to generate an effect, it will statistically succeed in generating a similar effect with future observers as well.

The nice thing about neuroscience is that it doesn’t matter how sensitive people are (not everyone perceives their variations in the same way). However, being that they are objective values, it is the predictive models that allow us to say whether the answer is significant or not. Here I would like to add a theme related to the TSW approach. You can look for many determining factors, in an emotional context, but as in all research it is necessary to narrow down the goal if you want to be effective. Our challenge is to identify the solutions that satisfy already existing needs in people. It is not about creating new needs. It is about understanding the ones we already have and trying to find the best way to satisfy them (without having to explain that the “buy button” is a deplorable illusion).

Daniel Limmer, Michael F. O’Keefe, Emergency Care, 10a ed, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Edward Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2005, p. 214.